Gallium Studios finds Will Wright’s memories game, Proxi, as hard to pitch as The Sims

When Will Wright pitched The Sims to his bosses at his own company years ago, he couldn’t get anyone excited about it. It was a miracle it shipped, and then it became the foundation for a franchise that has sold 200 million copies and generated $5 billion in revenues to date.

Wright has some deja vu today as he pitches Proxi, a game about memories that is unlike anything else in the market. It is highly original, but so different that potential investors in Wright’s Gallium Studios are gunshy about backing it.

“This is a boat I’ve been in before. I’m kind of used to being in this position,” Wright said in an interview with GamesBeat.

“We’re struggling with getting the product out there,” said Lauren Elliott, CEO of Gallium Studios, in an interview with GamesBeat. “Our story is about how hard it is getting brand new projects off the ground, particularly with larger publishers. There are parallels between Proxi and The Sims.”

The architecture and the ant simulations

Back in 1993, before Electronic Arts acquired Wright’s company, Maxis, there was a struggle. Wright had a stunning success with games like Sim City and Sim City 2. He wanted to move beyond sequels to a new project about people. But no one really believed in it. There was a focus group about the game concept, and most of the people surveyed — the majority of them were men — said they wouldn’t play The Sims.

“I don’t blame anybody, because it’s very hard to describe an idea as a designer and expect the people you’re pitching to reverse engineer that idea in their head,” Wright said.

This game would later be called The Sims. But Wright started out thinking about a game about architecture. A self-taught game designer, he had read books on architecture like A Pattern Language. It talked about patterns like why people normally sat in the back of church pews rather than the front.

“It started primarily as an architectural thing, and then we started realizing how fascinating the people were,” Wright said. “Then everybody had so much fun just messing with the people that we doubled down on that.”

Wright tried to make a lot of smart objects for his architecture game. And he figured the way to test whether they were good or not was to see if they could attract people.

“The people actually ended up being roughly modeled on what we had with Sim Ant, which I had just previously released. We tried to realistically do a dance by ants following pheromone trails,” Wright said. “All the ants are pretty dumb to begin with, but their intelligence is distributed through the environment, and so I was wondering if we could simulate human intelligence by distributing the intelligence to the environment rather than making the Sims really smart. That made the objects smart, and they told the Sims what to do and generate animations for actions.”

A Sim could walk up to a refrigerator and grab something to eat from it, if the conditions were right and the refrigerator did a good job of attracting a hungry Sim.

“The objects are advertising. If you’re hungry, come to me. And they’re matched up against the needs of the Sims,” Wright said. “They were originally there to score the architecture.”

So the team built a foundation where the objects inside a building were smart and the people were dumb. The objects would advertise themselves to the people, who would respond based on their needs and instincts. If the virtual person was hungry, they would be drawn to the refrigerator or the toaster.

“Basically, I had to fight for resources within Maxis,” Wright recalled. “Eventually, there was a group over in San Mateo that we had hired. It was what we called our core technologies group, and they were trying to figure out how to connect the simulations and all this stuff. It was like four really brilliant people, working on their own over there. But nobody was using what they made. They were coming up with all these plans for Sim World.”

At one point, Wright asked his higher-ups if he could take those four people. He got approval to do that from Maxis management, and then his team started making good progress on prototypes. But people had to use their imagination when they were evaluating the progress, as the prototypes weren’t that impressive; no one was that thrilled watching the Sims go to the bathroom.

Then, in 1997, Electronic Arts came calling. It wanted to buy Maxis, a public game company, and EA CEO Larry Probst and Don Mattrick visited for a due diligence check. Mattrick was Probst’s head of game studios, and they started talking to Wright. EA knew it needed to do a better job creating new franchises, and acquiring them was the next logical step.

Probst told me later he was shocked that Maxis wasn’t listening to Wright, the founder of the company, and wasn’t investing in his game. EA had been eyeing Maxis to acquired the Sim City franchise, which Wright had also created. Wright’s small team had a graphic programming language that they had used inside the objects, and this helped create the illusion that the Sim characters were intelligent. Wright could make the Sims seem smarter just by dropping new objects into the game.

“Don and I were like oil and water, and yet I really respect Don,” Wright said. “He saw The Sims prototypes. He had actually been working on something vaguely similar in EA, Keeping Up With the Joneses. When he saw the Sims, he said, ‘We need to buy Maxis for this, not for Sim City.”

The deal went through, with EA acquiring Maxis for $125 million in July 1997. After that, Wright pretty much got everything he wanted. It still took time to make the game, but the game debuted on February 4, 2000.

With Proxi, the meetings where the team makes a pitch are similar. On one occasion, Wright met with a team that knew him well. They loved the idea and the reunion with Wright. They showed how the memories could work. But they couldn’t quite figure out who the audience would be for Proxi. The presence of AI scared them a bit. There were ongoing conversations, but no result yet.

But big publishers now have different priorities. They need a game to come in at around 20 million copies sold for it to be worth their efforts. And so they couldn’t strike a deal yet.

“I don’t blame them. That’s just the way their company operates,” Wright said. “they just can’t figure out how to politically or financially sell this small team of 10 or 12 people, which has huge upside, to their superiors.”

EA’s own recent decisions are an interesting example. When EA bought BioWare ages ago, it was working on seven different games at once, with titles like Mass Effect and Dragon Age getting attention. Over time, as games became more expensive, that shrank down to just Mass Effect and Dragon Age. And after EA said Dragon Age’s launch was disappointing with 1.5 million copies sold, EA announced that BioWare would just work on one game at time. That pretty much means only Mass Effect, and no Dragon Age.

Back in the 1990s, Wright said game publishers were risk averse, and venture capitalists didn’t really invest in games. Now, the VCs are plentiful, but everyone has become risk averse again for different reasons, like the growing costs of making games.

Elliott worked on the Carmen Sandiego game series, which had about 25 titles and grew to a few hundred people. Then that company, Broderbund Software, refocused on fewer titles, led by sequels and not new franchises. It was sold to the Learning Company and underwent more changes.

Around 2020, new VC firms like Griffin Gaming Partners raised funds to invest in new original intellectual property, as that was a space the big game companies were abandoning. But the VCs were cautious, offering money in tranches, where startups had to hit milestones to get the next round of funds. But as the pandemic growth for games was followed by the post-pandemic bust, the funding dried up.

In 2022, Wright and Elliott did convince investor to pump money into Proxi, but the amount was limited. The money was there for ongoing prototype development, but Gallium Studios did not get the additional money to take the game to the market and handle publishing tasks. The idea was the company could raise the money after it hit some milestones. In August 2022, Griffin Gaming Partners announced it led a $6 million round for Gallium Studios.

“We were originally going to have the whole studio do our own marketing and do the whole nine yards,” Wright said. “Then four or five months ago, we decided to pivot that because we wanted to keep the studio around.”

Despite the ongoing effort to develop the game, it turned out the 2022 round was not enough to keep things going forever and help market the game for launch.

Griffin has now waited to see what kind of market validation the game can hit, but Gallium Studios is just about out of money to validate the title. By talking to GamesBeat, Elliott feels like a transparent article about the company’s struggle is the last chance to find funding.

“We’re right at that point where the team is at the end of our funds, and that’s just a fact,” said Elliott. “We’re being transparent about it. We had Griffin …” but the funding wasn’t enough to get the product out the door or cover the marketing costs.

“I need to get Will’s project out there, and we’re doing anything we can do,” Elliott said.

You would think that Wright’s own reputation would be enough to keep that money flowing, but it’s been hard to come by. At least one venture capital fund has said it will back Gallium Studios, but it told Wright and Elliott that they need to find a lead investor to complete the round and get the money.

Proxi is a game that let’s you look inside yourself

Meanwhile, Wright showed me a copy of the Proxi game back in December. He had just come off of a public demo of the game in support of Breakthrough T1D charity as it tried to raise money to help kids deal with diabetes. Wright had family and friends who had diabetes, and he helped draw attention to the cause. It is, as Wright says, a highly original game. There’s nothing like Proxi as far as I’ve seen, and it involves some fascinating concepts, just as we saw with Wrights other titles like Sim City, SimEarth, The Sims, Spore and more.

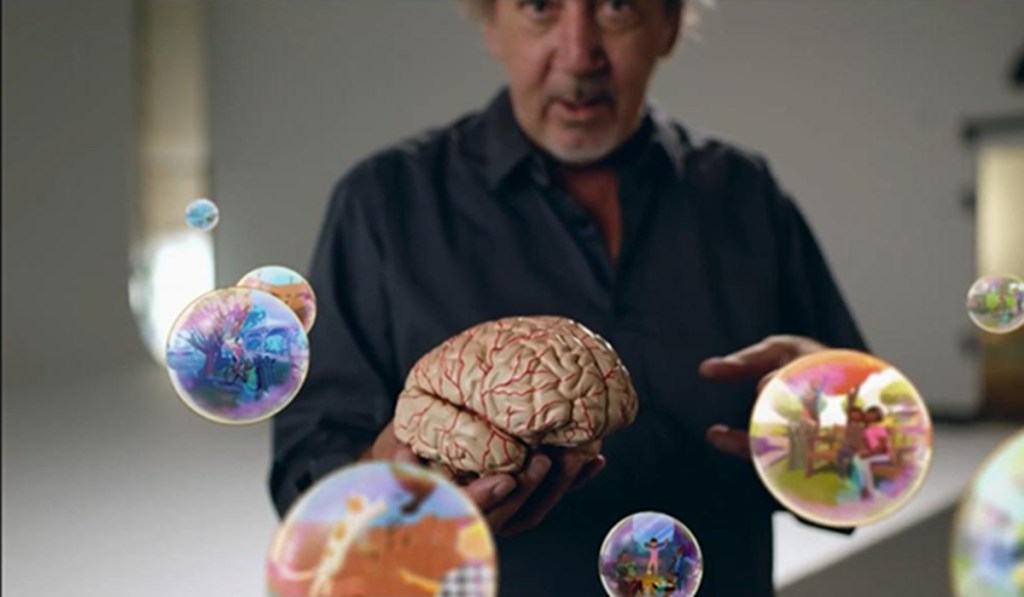

It’s kind of like a simulation of your brain. With The Sims, players could create characters who lived out fictional lives. Proxi is based on your real-life memories, as you describe them. Your words become part of a prompt for generative AI, which converts them into scenes that can be edited and explored in a kind of 3D world of your mind. It’s like your own memory palace, and each memory is like a snow globe.

You can add more memories to the world and connect them. And then you can also connect them to the shared memories of other people in your life and see the intersections with those people. And by stepping back and looking at these connections, Wright believes players will have moments of self-discovery and self-realization.

Proxi is inspired by theories about memory, subconscious processing and your feelings about your own personal identity. It’s based on the notion that thoughts and memories are stored in networks of associations. The notion is that the game can represent your id, or your subconscious self, and expose that to you on a conscious level.

Back in May 2024, Wright talked about this at our GamesBeat Summit 2024 event with Numenta CEO Subutai Ahmad. They discussed using Numenta’s neuroscience-based AI commercial solution, the Numenta Platform for Intelligent Computing (NuPIC), for its new game Proxi. Numenta was started by tech pioneers Jeff and Donna Dubinsky in pursuit of brain-based computing.

How Proxi’s gameplay is shaping up

Wright saw Proxi as a way to quantify your memories. He has been thinking about making a game about memories for a long time. What interests him is the storytelling around memories and how that can help us communicate with each other about our own life experiences. You can share your memories with friends and you can see where your memories intersect.

“As we turn the storytelling into gameplay, these stories want to become little game pieces. You’re manipulating, moving around, sharing the memories. And the more interesting we can make the game pieces to represent your memories,” the smarter it looks, he said. People can share memories as if they were stories inside snow globes. And people who participated in those memories can connect them to their own memories around similar events.

“One of the most fascinating parts, is going back and seeing all the memories that people shared about their high school,” Wright said. “I could have stories from high school about my German teacher, and other people, even strangers, may share those memories, which are geolocated. I can walk around my hometown on the memory map, and I can see someone put up a memory about how their mother met their father.”

I asked Wright why the character animations were lightly detailed and weren’t extremely realistic. He pointed to Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art book. I’ve read the book, and McCloud makes a point that if you make a character seem more abstract, it’s easier for someone looking at it to put themselves in the shoes of that character. The more abstract the character, the easier it is to identify with that character, Wright said.

Wright noted that that the animation of the memories can depend on generative AI, which is making huge strides in being able to generation 2D or 3D images based on a text prompt. The game could tap tools like Midjourney or Dali, as needed, so players can generate the images to go with their memories. Gallium Studios could tap its own team to get it started and have a uniform art style. But those things could exist side by side wit user-generated AI images.

Wright told a story about a memory about his uncle and him sailing on a lake. I would just look and find an image of the same kind of catamaran on a lake. And while it’s not an actual picture of me, it can still bring that memory to life, he said.

If a person got excited about the game, they could generate enough memories to fill up a big game space and it would be interesting to see how deep and intricate the memories can become. The game might tap something like spatial zooming to illustrate those memories in the brain. Some memories will be ore prominent than others and be bigger on the memory map.

Wright noted that Kevin Lynch, an urban planner, noted that everybody has around five or ten major landmarks in a city where they can reference everything. They can draw mental maps, and these mental maps are similar to the kind of images people could create with Proxi.

“You could put your memories on a map where you went to high school, and then you can find a bunch of other memories associated with that high school,” Wright said.

He noted that your world will be private and you can organize it as you wish and yet you can use things like your high school to share your memories with others. The memories are organized as people, places, time, feelings, things and activities. So you could build memories around your grandmother.

Given the importance of our memories, Wright has had to think about things like making the game last for 100 years so people can always have their memories.

Searching for a solution

In the meantime, Gallium Studios needs money. Wright and Elliott are seeking funding to finish the game. And they’re trying to get more publicity too. Wright recently did a Reddit Ask Me Anything (AMA) session, where he talked about Proxi and shared stories about it.

The game will be aimed at the PC, PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X/S. Wright explored doing something inside of a game world like Roblox, but hasn’t pursued the idea much.

At one point, Wright considered using the blockchain to get the assets in the hands of the user-generated content creators. Wright wanted people to own their memories, and things like piracy might necessitate the verification possible with blockchain. But Elliott said it didn’t work out from a functional standpoint. The transactions happened too slowly.

Proxi allows people to reminisce about their lives and recall their distant memories. There’s a lot of psychological value in doing that. It could be considered a game for mental health, and lord knows we as humans could use help on that front. But it’s getting to be do or die time for Gallium Studios.

Wright said the team has ideas like taking highlights of memories and making a trailer of someone’s life. You could share that around and see how popular it can be. Wright said it isn’t necessarily the volume of memories that counts. Rather, you might try to organize your thoughts so you can come up with the 10 most important memories of your life. That means you can triage and prioritize moments in your life, and you might be able to learn something about the pattern of your life.

“You wind up remembering things that were related, and then you want to put in memories faster as they keep sparking other memories,” Wright said. “I found that I was getting interesting results after just adding two dozen memories. When you get to 100 memories, it’s really fascinating.”

From the fundraising process, Elliott has learned some harsh truths.

“My net learning is that the current trend for established publishers is away from taking chances on new ideas, and simply putting more money into marketing — which is counter productive if you look at where the new ideas are coming from,” Elliott said. “AI is pumping heavily into the industry — AI generative content, coding agents, marketing agents, no-code platforms etc. which, if aimed in the right creative direction, will inevitably make for a new gen of successful small companies — I believe able to challenge larger publishers.

He added, “EA’s marketing budget was up 4% or 5% last year – to about $1 billion, this increase alone would have funded 10 new companies. Maybe the AI companies should form their own game studios.”

Whatever happens, there are a lot of people rooting for Wright and Elliott, who have accomplished some great things in the past and somehow always managed to surface amazing original works of divine creativity.